Yeet your phone

I should have written this one ten years ago

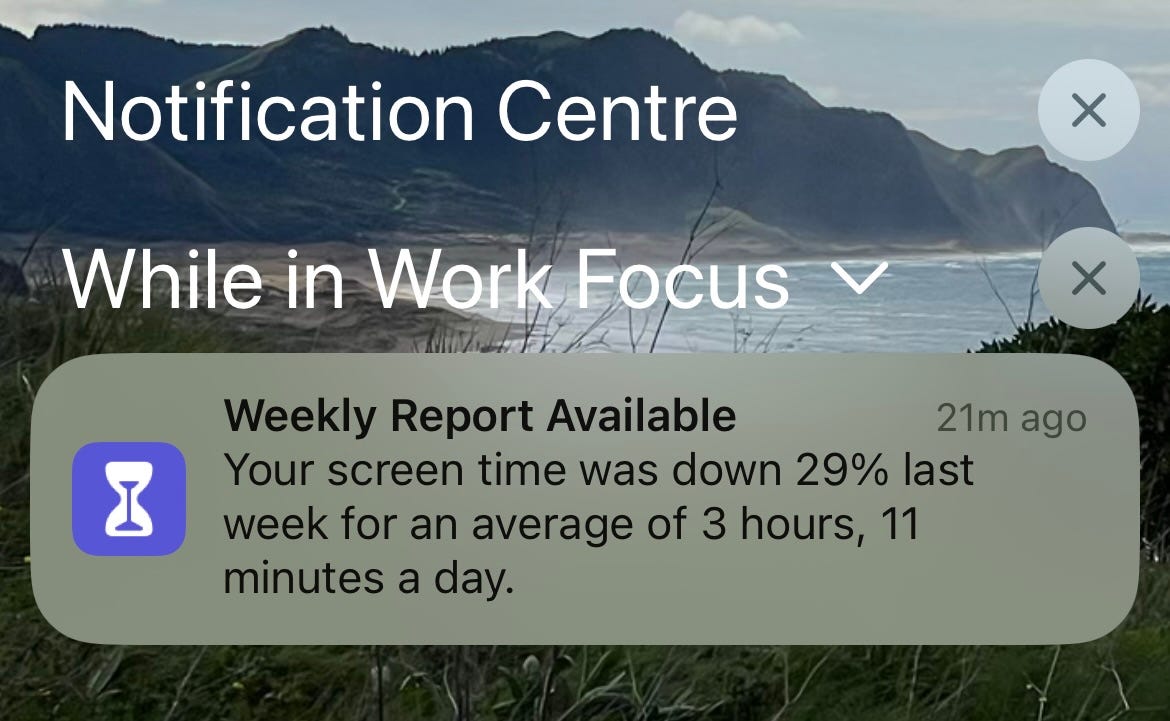

A few weeks back, I noticed my iPhone screen-time averages were starting get a bit silly. Like a lot of smartphone users, my device is set up to passively scold me for how long I use it, and last week it informed me that my use time was down slightly to an average of just… three hours a day.

This meant my average time the previous week was close to four hours a day.

“I had my reasons!” I reasoned. There are lots of apps I use for work — Gmail, Slack, others. I’d written a time-consuming and fraught article on Christian Zionism for Webworm and I’d spent a lot of time popping in on the Substack app to check on the comments. And there was, uh, Instagram. Gotta check the ‘gram, right? How else would I know what my rapidly ageing millenial cohort were up to?

But four hours seemed excessive.

At the risk of pointing out the obvious, there are only 24 hours in a day, and 8 of them (if you’re lucky) you spend asleep, so four hours is… a lot. There’s lots of other things I want to be doing, not least of which is consistently updating my self-improvement newsletter.

I started writing this article, and then I was taken with the sudden urge to Do The Maths.

It was very depressing, and it went like this:

Let’s assume I’ve spent three hours a day on a smartphone since I got my first one. It was more than 10 years ago, but we’ll be generous and allow for just one decade of smartphone use. What’s more, we’ll say that I only used it for three hours a day for six days a week. Inventing a kind of smartphone Sabbath should allow for any days I used it less than three hours.

So. There are 52 weeks in a year. Multiply 52 by 6 and that gives us 312: how many days I use my phone in a given year.

(Ironically, I am using my smartphone’s calculator app to do these calculations.)

Multiply 312 by the 3 hours a day I use my phone and I get 936. Nine hundred and thirty six hours a year.

Shit.

Let’s multiply those 936 hours by 10 years and that gives us… 9,360 hours over the last decade. God.

How many total days is that?

Break out the division. 9360 hours divided by the 24 hours in a day will give us the total number of days.

It’s 390.

Three hundred and ninety days.

Fifty-five weeks and four days.

About one year and one month.

It’s the equivalent of being on my phone continuously, day and night, without stopping, for more than a year.

What?!

I must have the maths wrong. I check it with my wife. She’s a primary school teacher, this kind of maths is her bread and butter.

(At this point I really did go upstairs and check the preceding paragraphs with Louise.)

Unfortunately, I am right.

It’s not just me. And it’s not just you. Estimates of average daily smartphone use vary, but reputable studies put it at between 2 hours a day (at the low end) and almost 6 hours a day (at the high end.)

What’s more, the only thing more popular than smartphones might be the desperate search to disconnect from the damn things. Scratch the surface and the articles are everywhere: “Device-addicted parents struggling to curb kid's screen time,” worries an RNZ headline, with a buried lede that parents are struggling even more to curb their own screen time. Linked in the RNZ story is a piece by NYU professor John Haidt with the (contested) theory that “Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls.” Meanwhile, the Spinoff has a helpful power ranking of all the ways writer Madeleine Holden has tried to curb her own smartphone addiction, and advice columnist Hera Lindsey Bird has a …broad spectrum of suggestions:

There are easy things you can do to limit how interesting your phone is. Mute all but essential notifications. Make everything grayscale. Kill every potential source of dopamine. You could get an alarm clock, or even better, a clock radio. You could charge your phone in another room. You could swap your phone for a fax machine. You could swap that fax machine for a water blaster, and comprehensively clean all your walkways.

Take all these anecdotes of compulsive use, add users’ desperate desire to quit, and you’ve got something that looks a lot like an addiction. There are plenty of people who’ll tell you that this waddling, quacking bird is definitely a duck. If you’ve ever searched the topic you’ll be familiar with explanations like this one from Stanford professor Anna Lembke, who suggests our smartphones have turned us into “dopamine addicts.”

"We can very quickly then get into this vicious cycle, where we're not reaching for something to feel good, but rather to feel normal or to stop feeling bad."

Continuous over stimulation of the brain's pleasure pathways worsens the situation, she says.

"If I continue to bombard my brain's reward pathway with these highly reinforcing drugs and behaviours, I eventually end up with so many Gremlins on the pain side of my balance, that not only do I need more and more to get the same effect, but when I'm not using, I'm in a dopamine deficit state, I've got a balance tilted to the side of pain.

"I experience the universal symptoms of withdrawal from any addictive substance, anxiety, irritability, depression, insomnia, craving. And I will then seek out that drug not to feel pleasure, but just to stop feeling pain."

It seems clear that smartphones can be addictive, but there’s always the danger — as so many self-taught self-improvement influencers do — of biffing babies out with the dopamine bathwater. Thanks (ironically) to my unhealthy YouTube habit, I’m exposed almost constantly to people who pick up the notion of “dopamine fasting” and run off a cliff with it. To make some points that should be obvious: Smartphone use is not a closed loop, there are an infinity of things that make people happy or sad that predate smartphones by a few hundred thousand years, and you need dopamine to live. The list of extremely legitimate reasons to use smartphones is long. In many countries, the villages that we need to live and work and raise children are all but gone, and in place of spaces where we walked and talked together are a billion lonely boxes, each containing social creatures with a desperate need to reach out. If you can’t do physical, then digital will do. If you’re a new mum, nap-trapped by an infant, sending memes to your mates might be what’s keeping you sane. And if you are an activist or a journalist or a politician or an artist or one of any number of things, a huge part of your job takes place in online social spaces, and you need to Post.

And for years, that’s what I’ve told myself: I’m an artist, and I write, and I need to be online. Reading an article or ten feels like virtous work, as does scrubbing through a tutorial on YouTube. What I watch is often deeply entwined with my identity. And it has to be said that screens are, in many ways, wonderful. During the pandemic, I could keep in touch with family and friends all over the world. My son knows his grandparents and cousins by sight; in ye olden 90s we would have made do with voice-only phone calls, photos and (if we were lucky) a videotape. Having all the world’s knowledge, a high-powered camera, and even a calculator (take that, maths teachers) with me at all times is a boon.

Yet. These days, as I scroll, it’s accompanied with the feeling that I’ve been conned. Looking at the numbers, it’s clear: I’ve spent more than a year of my life on smartphones and the return on investment is terrible. You could excuse the sheer amount of time spent if there’d been something to show for it — a big social media presence, the ability to code, learning a language on Duolingo, a consistent output of pretty much anything creative. But I can’t make any of those claims. I know life is about much more than “productivity,” but even with that caveat my phone time is staggeringly unproductive. I post perhaps twice on Bluesky or Mastodon on a big day. Instagram is maybe once a week. Nearly all the time I spend on my phone (and, if I am being honest, my computer) is in passive consumption. Lurking. I don’t have many good memories of the half of my life I’ve spent on screens, or in fact any strong memories at all; it’s all one amorphous, algorithmic blob of memes and blogs and socials and takes.

My first thought on doing all those calculations was: how am I even finding the time to use my phone this much? I’m busy. I have a demanding day job. I have a social life. I’m a dad to a toddler. I cook and clean and walk and go to the gym. There’s practically never a time when I am on my phone for more than 20 minutes at a stretch. I think I could count the times I’ve spent more than an hour in one session on one hand.

But a bit of thought solves the not-mystery.

It’s the in-between times. 5 minutes here. 15 minutes there. Opening the phone to a notification of a text from a friend only to open Insta to be reminded of a meme you want to send to another mate but only after watching a mildly interesting reel lifted from someone else’s Tik-Tok. It adds up quickly.

It is, to age myself with a simile, like changing gears in a manual car. If I’m finishing a task (let’s say, the weekend morning dishes) and I need to do something quite different (let’s say, go to the gym) a nice smooth gear shift will have me picking up heavy things in no time. But add my phone to the mix — a quick reply to a mate, an email check to see if that package has shipped yet (hope, nope), scrolling to pick the right playlist or podcast, pausing to download an audiobook — and it’s like leaving your car to idle in between gears, eventually to slow down or stop. Suddenly it’s 25 minutes later and getting a full workout in before I need to take my son to his appointment is impossible. May as well not go!

This sort of thing happens all the time.

It seems frighteningly obvious that the life I want to live is being eaten by my smartphone screen.

In fact, it’s so obvious that the only reason I can think of for not giving it due attention is because of how frightening it is.

I felt like a character in a whodunit who’d always known who dun it but was too scared to admit it.

And that’s just smartphones. Once you add TVs and computer screens to smartphone use, things get scary. Time spent on screens goes from a worryingly significant fraction of life to the overwhelming majority of it, to the point where the words “HE LOOKED AT SCREENS” would make a cruelly accurate epitaph.

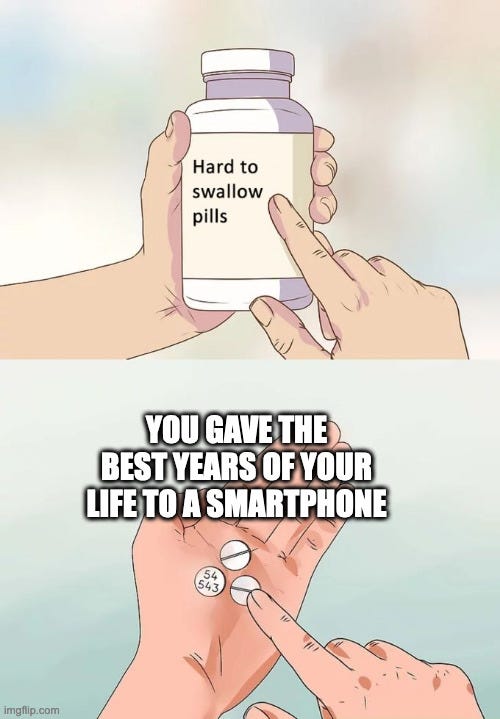

My brain’s so cooked by it all the only way I can visualise it is in meme form:

Here’s the thing: for all the advice richocheting around the Internet on how to curb your Internet-adjacent addictions, there’s probably only one thing for it.

Cal Newport, the irritatingly fresh-faced author of a couple of self-help books I’m sure I’ll get around to reviewing one day, puts it succinctly. (You don’t have to watch the whole video. This clip should start it right at the relevant bit.)

Yes, that’s right. The answer was right there in the Book of Mormon1 all along.

Just… turn it off.

I took the medicine. Just before I started writing this article, I deleted all the social media apps from my phone. Twitter? X’d it. Mastodon? Mastadon’t. Bluesky? I blew it right off. Reddit? More like didn’t read it. Instagram? Instagone.

I wish I could say that I felt better instantly but it’s been several days now and I’ve felt twitchy and tired and I keep picking up my phone and putting it down for no reason at all.

If smartphone use is an addiction, this seems about right for withdrawal symptoms. I’ll say this: it does feel startlingly similar to when I quit smoking.

I don’t expect my productivity to suddenly peak. I’m an accomplished procrastinator; life will find a way.

But if I can get those lost slices of life back — those moments of necessary boredom, of smoother gear-shifts in between tasks, of seeing my son playing instead of gazing into the abyss of my phone and having it algorithmically gaze back — then it’ll be worth it.

I’ll let you know how I go. If you decide to do something similar, I’d love to hear how you manage.

EDIT: Annoyingly, I just found out I accidentally sent this newsletter out with comments for paid subs only, which is the Substack default, and wasn’t my intention. I’ve fixed it now, so comment away!

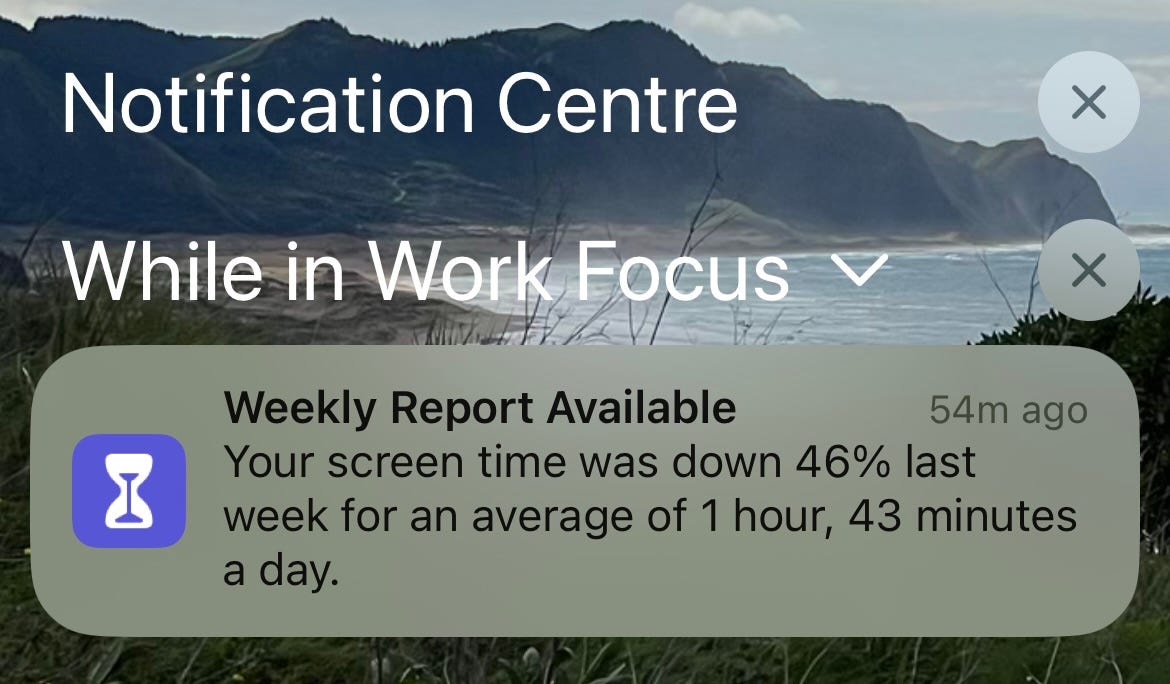

Also I got this notification this morning. It’s still too much, but it’s a big improvement. The system works!(?)

For entertainment purposes, if by “entertainment” you mean “being crushingly depressed,” I have made a spreadsheet you can use to calculate your own abyss-gazing tendency: how many years of your life it’s taken to date, and how many it will remove from your future. Just put your age in years in cell B1, how many years you’ve had your smartphone in cell B2, and your average daily hours of smartphone use in cell B3. Enjoy!

Yeet Your Phone: The Spreadsheet.

The stage musical, not the actual book. ↩