I found the Überman

Gidday Cynics,

Remember “life-hacks?”

Today, life-hacking is a cutesy phrase that means anything from “make your bed after showering” to “rip the the transformer out of your microwave and use it to burn patterns in wood and/or instantly stop your heart.” But this term has its origins in the idea of actually hacking your life — and for a while, back in the ancient times of around 2012, the ultimate in life hacking was sleep hacking.

If, like many people, you feel like you don’t get enough done, the appeal of hacking sleep is easy to see. Of course, for most of us it never progresses beyond an idea, because — as anyone who’s ever pulled an all-nighter, suffered from insomnia, or attended a needy child knows — not getting enough sleep sucks. But for some, here at last was a way to claim a third of their lives back. The last enemy of productivity had fallen! Sleep had been defeated! Tim Ferris’ The Four Hour Body captures the spirit of this attitude to sleep:

“Is it possible to cut your total sleep time in half, yet feel completely refreshed? The short answer is yes… Think of the books you could read, the things you could learn the adventures you could have with an extra six hours per day. It would open up a new world of possibilities,” Tim writes. He outlines several techniques for “polyphasic” sleep, with the most extreme being never sleeping for more than 20 minutes at a time. You spend all day, and all night, awake, and snatch sleep in strictly-regimented naps. Apparently, this would allow you to not only function but thrive. The catch? If you miss a nap — or oversleep — it screws everything up, and you have to adjust all over again.

This sleep-hack was called the Uberman, and it won legions of raving fans online. Forums and subreddits sprang up to discuss sleep-hacking, and the media took note, enought to drive the idea of sleep hacking into — if not the mainstream — then perhaps a minor tributary.

This sleep-hacking craze didn’t escape me. Thanks to my own well-documented issues with insomnia, it wasn’t something I wanted to try, but I couldn’t let it go. Years after sleep hacking faded into relative obscurity, I decided to find out more. Who would come up with something like the Uberman — and why?

After a bit of minor sleuthing, I found the Uberman.

Her name is Marie.

The Uberman

At first, Marie was reluctant to talk — she’s had problems with the reporting on her sleep experimentation in the past, including an outlet publishing her last name when she’d specifically asked to remain anonymous — but after reading my account of fighting sleep and losing, she agreed to an email interview. It turned out that the reason she started experimenting with sleep was that she’d struggled with it, too.

“I always had trouble with sleep, and it got really tough in my teen years,” she explains. “I had really nasty, constant nightmares, night-terrors, sleepwalking, and something called "sleep confusion" where I would have a really hard time shaking off my dreams when I woke.”

Marie moved away for college, and soon found herself more desperate than ever. Insomnia would keep her awake for days, and then she’d sleep for 14 hours or more. This pattern repeated endlessly, making her miserable. She needed sleep to pass her classes, and wanted the long nightmare to end — literally — to the point that she was ready to try something extreme. When Marie complained to a friend that she could doze off easily, only to wake up around 20 minutes later and be unable to get back to sleep, her friend suggested: what if she just did that intentionally?

The schedule Marie’s mate suggested was based on the self-experimentation of Buckminster Fuller, best remembered for inventing the geodesic dome. A 1943 Time article strikes a blissfully optimistic tone about Fuller’s “Dymaxion sleep” method:

Fuller trained himself to take a nap at the first sign of fatigue (Le., when his attention to his work began to wander). These intervals came about every six hours; after a half-hour's nap he was completely refreshed… For two years Fuller thus averaged two hours of sleep in 24. Result: "The most vigorous and alert condition I have ever enjoyed." He wishes the nation's "key thinkers" could adopt his schedule; he is convinced it would shorten the war.

Other mercurial geniuses are said to have got by on only a few hours sleep, and there are hints that they employed similar methods to Fuller; both Nikola Tesla and Leonardo da Vinci employed frequent naps and supposedly slept only a few hours in a given day (or night.) These nap-based patterns are usually called polyphasic sleep, and there are other kinds too. The standard eight hour sleep we’re all urged to get is monophasic, taking an afternoon siesta followed by a later bedtime is biphasic, and there are variations in between.

After researching Dr Fuller’s approach, Marie figured she had nothing to lose, and potentially a lot to gain. “I was motivated by mad hope,” she says.

Marie began her version of Dymaxion sleep, and swiftly descended into a kind of hell.

“The schedule is extremely extreme,” she says. ‘It's probably the most restrictive sleep schedule possible, hell yes it's extreme. I've had a physical freaking baby and I can honestly say that adjusting to that sleep schedule was harder to get through than labor.”

Others have found the schedule similarly punishing. Take the account of Mark Serrels, who tried it back in 2012, and began hallucinating, blacking out, and otherwise losing his mind. He vlogged all of his experiment, and his final entry is disturbing, like something out of a low-budget horror film; he gropes around frantically for his lost time while slurring and stumbling over his words. After his blackout, he (sensibly) quit. “I stumbled into my bedroom, curled up next to my wife and collapsed into the most profound sleep of my life.”

But Marie made it. After adjusting, she found herself with a new lease on life. The nightmares and other sleep issues vanished. Her classwork improved. And notwithstanding the need to nap every few hours, she had so much more time.

“I compulsively write things, so after I'd done it for about 6 months, I wrote up my schedule.” Marie, a philosophy student, called the method Uberman, in a riff on Fredrick Neitzsche’s Übermensch, and posted it online. It went viral — a remarkable achievement on the internet in an age before social media..

“I got flooded with email, because unbeknownst to me, what I’d written up wasn't really information that was on the Internet yet,” Marie remembers. “So I threw up a website to track the answers I was giving by email, and then wrote a book to collect it all.”

Things were good. The schedule was working, Marie’s blog was a centre of discussion on sleep-hacking, and the Uberman became the accepted name for extreme polyphasic sleep.

“I collaborated with a bunch of lovely also-weirdos and tried a bunch of other nap-based schedules, collected tons of information on managing the difficult process of adjusting schedules, and so on,” Marie says. “In 2012 I did a second edition of the book, and I've done a smattering of other things, like talks and panels and interviews and one time an episode of a TV show, called Going Deep with David Rees.”

But there were downsides.

Life-hacking was having a moment and, with books like The Four Hour Body, people were embracing the idea that anyone could push their body in any desired direction, if only they had enough willpower. Marie resisted it strenuously: every chance she could, she pointed out that the reason she’d done her sleep experimentation and adopted an extreme schedule wasn’t to chase ultra-productivity — it was to defeat her sleep demons.

“The thing I've felt most weird about in others' treatments of polyphasic sleep was that somebody would always want to make it work for everybody,” Marie says. She suspects the primary motivation behind this take on her work was money, not curiosity or genuine need.

“Because, gee, everybody is such a huge market and if everybody gave us a dollar, how many dollars would we have?” Marie says, rhetorically. “When things go that way, I spend all my time insisting ‘yeah, but I'M WEIRD’ and saying ‘Everybody is different! Probably especially with sleep!’ and other things that feel obvious. I said it plenty, in the book and repeatedly on the site and in interviews, and yet there's always somebody who turns green and says, "what if this is the secret everybody is looking for?’”

Over the years, Marie’s become adroit at deflecting the weirder approaches, and says her experience with the sleep-hacking community she helped create has been overwhelmingly positive, but toxicity is hard to ignore completely. “I've experienced people wanting to misinterpret and hyperbolise what I did, for financial greed and other reasons, I've been the subject of some weird fights about gender (because most folks thought I was a dude and some made arguments based on it) and even some light stalking.”

Light stalking! Sounds horrific. Asked what the deal was, Marie is straightforward: the problem is a certain kind of person, who weaponizes the urge for self-improvement and productivity in order to put themselves on a pedestal from which they might be able to make money. In other words: tech bros.

“Tech bros suck from every angle. A lot — maybe over 95 percent — of the toxicity I've dealt with has been from tech bros,” Marie says, adding that as a woman working in tech she’s been the “only chick on the team” far too many times.

“I think it's because the way they think of ‘productivity’ is a harmful, exploitative concept. You have to be really clueless to go from ‘maybe I can do better if I work hard on myself’ to ‘...and then we should sell it and gain followers and everybody will think we're cool,” Marie says. “You have to be at least half-evil to be willing to bend the truth to make the second part work.”

Marie is disappointed that the bad aura of would-be and actual self-improvement influencers can put people off, but she says it helps to remember that tech bros aren't genuinely interested in any of the topics they put forth on, whether it’s coding software or self-improvement. “Rather, they're all wannabe-CEOs who will generally grab onto anything new and cool and try to make an empire out of it. My lack of interest in having any kind of empire was probably frustrating for some of them — and others were just frustrated over something, and then acted like crybabies because they had exactly the emotional maturity you'd expect from a wannabe-CEO.”

She’s quick to add, though, that the majority of her discussions on the topic were positive, and that the few that did become toxic were dealt with through the time-honoured block-and-mute. “I will say that insofar as there were arguments with specific people, they were mostly minor, and mostly easy to extricate myself from — the Internet is a wonderful place to mute people forever and forget they exist, and I've enjoyed doing just that with pretty much every tech-bro I've met, through my sleep experiments or otherwise.”

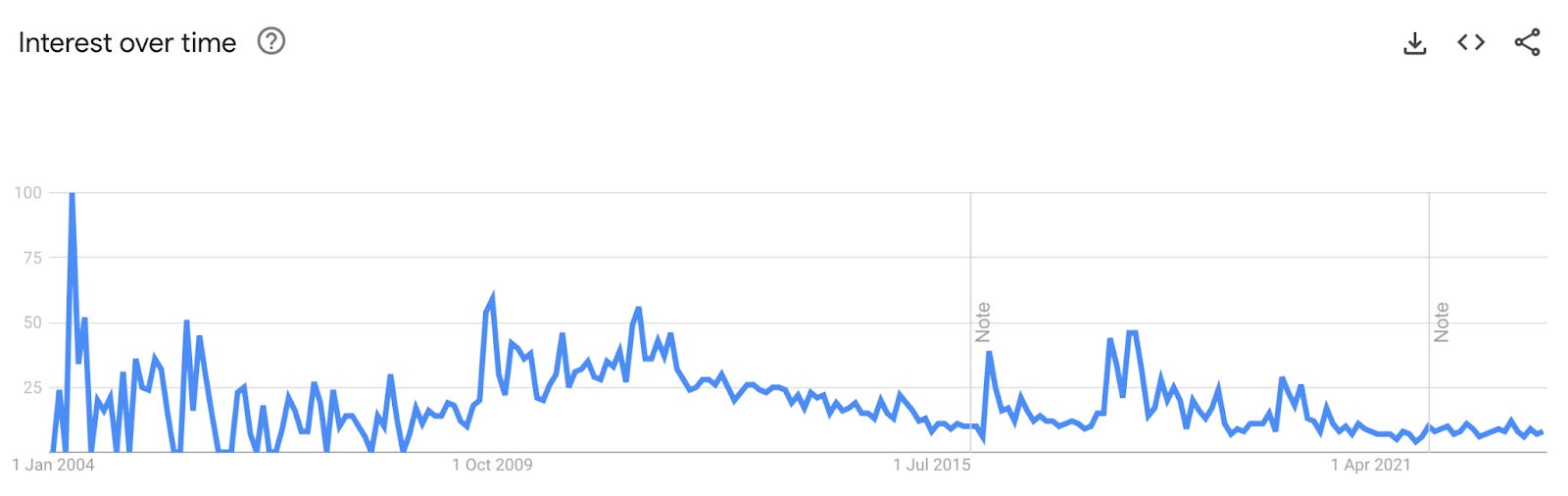

Over time, the furore around sleep-hacking died down. Google Trends shows interest in the Uberman and related terms slowly trending down, with occasional spikes of interest when a book, TV show or other influence makes the topic go viral.

Now that things have settled a bit, how is Marie doing with the Uberman routine she named and popularized? Much like Buckminster Fuller, who quit when his “Dymaxion sleep” proved incompatible with the rest of humanity, she doesn’t do it anymore. “I didn't keep it as my permanent schedule, because it's impossibly strict. Again, that makes it good for some things, but just for daily life? When you need flexibility and can't guarantee that you won't, say, catch a cold and then have to re-adjust to your schedule afterwards?” These days, she finds the “Everyman” routine (a 3, 4 or 6 hour sleep routine, punctuated with up to three daytime naps) most accessible — but her interest in all things sleep, be it monophasic, biphasic, polyphasic, or whatever, is undimmed.

Asked if she worries that her approach (or the publicity it gathered) might be risky, or encouraging people to sleep less than normal, her reply is thoughtful.

“Less than normal is a tricky concept, because the ‘norm’ is a broad range in humans. Some people simply don’t need more than a few hours of sleep, and many need more — I have a friend who must have 10 hours,” she says.

And that need isn’t immutable. Lots of things can affect how much sleep people need, want or get. These factors vary from common to rare, and include events like: childbirth, parenting, shift work, going to war, and sailing solo around the world. “So a wide range is normal, but my real point is that polyphasic sleep is about more than just sleeping less. This is another thing I often fought the tech bros on, because sleeping less sounds sexy and purchasable,” Marie says.

Ultimately, she advocates getting better sleep, which can look different across individuals and cultures — and is something that industrialised, Western society is terrible at making space for. In particular, the need to work or study at inflexible times means many people are forced into sleep schedules that don’t suit them. This is something that nearly all sleep experts seem to agree on. Teenagers, for instance, tend to have quite different circadian rhythms to children and adults, with late bedtimes and late waking — but they’re often required to attend school at a time when biology says they should be asleep. Parents are forced to return to work when truly adapting to their baby’s (polyphasic) sleep rhythms would require them to nap during the day. These systemic problems require systemic solutions, and aren’t something that can easily be monetised or turned into a product.

“Sadly for the tech bros, the fact that you can get better sleep by napping isn’t something you can really sell,” Marie says. “In fact, you end up saying ‘OK but then we need workplaces and public spaces to go along with this health-and-wellness need people have,’ and those are unpopular conclusions for anyone looking for their angle to get rich on.”

That’s the essence of her message: different people have different needs, and in the absence of an inclusive society that makes space for these differences, people might have to experiment to find out what best helps them manage. Ultimately, she feels her experience was worth it, so long as no-one else feels like they have to emulate it. If it’s not broke, don’t fix it — but if they’re struggling with sleep already, like she was, and want to try something different? Go for it.

“I can be — and feel — just fine on six hours of sleep if I get a midday nap, and I think that is a really cool thing,” Marie says.

Alright, Josh here again, although now I think about it I wrote all the stuff up there so I suppose I never really left.

I find this sleep-based self-improvement stuff absolutely fascinating, and I hope you’ve enjoyed it too. I really appreciate Marie giving up a bunch of time to write really detailed replies to my questions, and I think she’s ultimately got a good outlook on sleep: if you can, figure out what works best for you. Of course, as she points out, many of us are forced into sleep circumstances we wouldn’t necessarily choose. I doubt many new parents are thrilled to get up dozens of times a night. I’m naturally a night owl, and if it wasn’t for my son I’d probably favour getting a nice early midnight and waking up at 9 AM.

So does this mean I’ll be trying the Uberman any time soon? Dear God, no. It sounds like a baleful curse of eternal waking. Extreme sleep routines have been studied and are, in the blunt words of one study’s authors, not recommended. What’s more, my own early efforts to wrestle sleep into submission kind of fucked up my life. I don’t fancy rolling those dice ever again.

Should you try the Uberman? Obviously, it’s up to you, but if you sleep well (or even half-decently), I don’t know why you would. As Marie points out, chasing the deeply boring dragon of “increased productivity” is a bad reason to experiment with your sleep. However, if you find yourself forced into situations that require extended wakefulness, then perhaps being a bit more intentional about how you approach naps might be helpful. If nothing else, it’s good to remember that when you’ve had a shit night’s shut-eye, a quick snooze might be all the medicine you need.

There’s a part two to this piece coming up soon, because as I’ve hinted, there are lots of people who are essentially doing the Uberman — but not by choice. And I want to make sure their voices get heard.

As always, thanks for reading. This newsletter is free, so if you’ve found this piece valuable, please hit the “share” button, or — if you’re reading this in your email — feel free to forward it to a friend.